Seroma Formation

The development of seromas following this procedure is usually associated with multiple-level fusions on older patients with little muscle atrophy of the ventral cervical muscles that require more extensive dissection and retraction. Although drains can be used, the majority of cases resolve with time and without constant aspiration or lancing. If the seroma develops into an abscess, open drainage is encouraged to try to reduce the seeding of the implant with bacteria. Effective control of hemorrhage and usage of suction helped to keep the number of postoperative seromas as low as 3% in our clinic over the past 4 years.

Infections

The incidence of postoperative infection of the soft tissues or the implant is very low (<1%). Soft tissue infection usually produces a febrile response with a firm, painful enlargement at the surgical site, leukocytosis, and increased fibrinogen concentration. Treatment consists of drainage (best done with ultrasonic monitoring), application of appropriate antibiotics, and hot packing. Infection of the implant would produce the same clinical response. In addition, the patient is unwilling to move the cervical area and may show increased neurological signs compatible with meningitis. This author's experience is based on one case of suppurative meningitis (from infection with KLEBSIELLA). A postoperative myelogram taken when the patient was tetraparetic demonstrated a uniform narrowing of both dye columns of the entire cervical area. The case was resolved after retrieval of the implant and the application of a methylmethacrylate bone cement that had a cephalosporin antibiotic powder added before it was mixed with the catalyst.

Fractures

The occurrence of fractures of the adjacent vertebrae at the time of surgical implantation or during the immediate recovery period is less than 1% and is generally related to over-drilling the implant hole, leaving only a thin plate of bone between the end of the implant and the spinal canal. In such cases, the resulting structure can not withstand the forces that a violent recovery or a severe fall during the early postoperative period exerts. In most instances, the only clinical signs associated with non-displaced fractures are an increase in the rigidity of the neck.

Severe fractures can result in clinical signs that range from paralysis when the displaced fragments cause severe cord compression to an obvious seroma formation and ventral displacement of the trachea as the implant migrates ventrally because the rigidity of the drill site has been compromised.

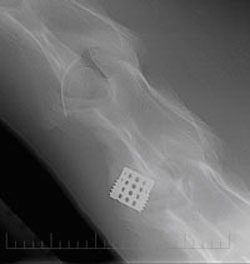

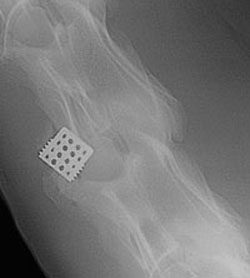

Fractures are confirmed by radiographic examination, although the subtle fracture lines may be difficult to detect immediately, requiring repeat radiographs after 10 days. It may be necessary to perform a myelogram to determine whether or not the spinal canal diameter has been compromised.

Conservative treatment is indicated in most cases because revision with unstable vertebral bodies is very difficult, and the majority of cases have resolved with the passage of time. The image displaying the fracture weeks following surgery shows the healing process with conservative treatment and stall rest.

Complication Rates

Minor complications associated with this procedure include ventral migration of the implant, laryngeal hemiplegia, and Horner syndrome. Ventral migration was found in 3.5% at postoperative radiographs and tended to occur within the first 7 days after surgery 9.

The risk of laryngeal hemiplegia was less than 1%, and transient Horner syndrome was observed in 1.5%. Fatal complications would include esophageal rupture (1.5%), laryngospasm (0.8%), and fractures (0.8%).

Recent results show that the partially threaded cylinder (the Seattle Slew Implant) implant procedure if correctly performed, does allow for a faster fusion and reduces the chances of vertebral fractures and ventral migration that has been associated with the Bagby Bone Basket.